This chapter provides information about:

- Pre-vaccination: cold chain management, informed consent, pre-vaccination screening, contraindications, spacing of doses, catch-up, and adult vaccination (section 2.1)

- Vaccine administration: preparation, route, vaccination techniques by age, and multiple injections (section 2.2)

- Post-vaccination: post-vaccination advice, pain and fever recommendations, anaphylaxis and emergency management, and documentation and insurance (section 2.3).

Who can administer a vaccine?

Vaccines can be administered by:

- a nurse practitioner

- a medical practitioner

- a registered midwife

- a designated prescriber (which includes a registered nurse fulfilling the designated prescriber criteria)

- a person authorised to administer the medicine in accordance with a prescription or a standing order

- a registered pharmacist and a registered intern pharmacist (who has completed approved training on vaccinations)

- a person who is authorised by either the Director-General of Health or a Medical Officer of Health under Regulation 44A or 44AB of the Medicines Regulations 1984 (see A3.6)

- a person authorised as a vaccinating health worker by either the Director-General of Health or the national Medical Officer of Health under Regulation 44AB of the Medicines Regulations 1984 (see A3.6).

The vaccines a person may administer will vary depending on the lawful basis upon which they can administer a vaccine or vaccines (see A3.6).

2.1. Pre-vaccination

The ‘Immunisation standards for vaccinators’ and the ‘Guidelines for organisations storing vaccines and/or offering immunisation services’ apply to the delivery of all Schedule vaccines and those not on the Schedule. See Appendix 3.

The vaccinator is responsible for ensuring all the vaccines they are handling and administering have been stored at the recommended temperature range of +2°C to +8°C at all times (see section 2.1.1 ‘Cold chain management’ below and National Standards for Vaccine Storage and Transportation for Immunisation Providers 2017 (2nd edition).

Information on vaccine presentation, preparation and disposal can be found in Appendix 7.

Vaccinators are expected to know and observe standard occupational health and safety guidelines to minimise the risk of spreading infection and needle-stick injury (see Appendix 7).

All vaccinations on the New Zealand National Immunisation Schedule are given parenterally (by injection) except for the rotavirus vaccine which is given non-parenterally (orally). For non-parenteral vaccine administration, follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.1.1. Cold chain management

2.1.1. Cold chain management

All vaccines must always be stored and/or transported within the recommended temperature range of +2°C to +8°C.

See Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora Cold chain standards for vaccines website for further details on vaccine storage and the National Standards for Vaccine Storage and Transportation for Immunisation Providers.

The ‘cold chain’ is defined as ‘the system of transporting and storing vaccines within the recommended temperature range of +2°C to +8°C from the place of manufacture to the point of vaccine administration (the individual)’. The integrity of the cold chain is dependent not only on the equipment used for storage, transportation and monitoring but also on the people involved and the processes/practices they undertake.

Table 2.1: Key points for cold chain management

|

All vaccinators are responsible for ensuring the vaccines they administer have been stored correctly. |

|

All immunisation providers storing vaccines must use a pharmaceutical refrigerator. |

|

The pharmaceutical refrigerator minimum and maximum temperatures must be monitored and recorded at the same time each working day. |

|

All immunisation providers must monitor the refrigerator with an electronic temperature recording device (eg, a data logger) that records and downloads data on a weekly basis. This should be compared with the daily minimum/maximum recordings. |

|

All immunisation providers who store vaccines and/or offer immunisation services must achieve Cold Chain Accreditation. |

|

Each immunisation provider must have a written cold chain management policy in place and ensure their policy is reviewed and updated annually. Each vaccinator is responsible to ensure they are able to access this policy, as it will contain important practice information on vaccine storage. |

|

If the vaccine refrigerator temperature goes outside the recommended +2°C to +8°C range

|

2.1.2. Informed consent

2.1.2. Informed consent

What is informed consent?

Informed consent is a fundamental concept in the provision of health care services, including immunisation. It is based on ethical obligations that are supported by legal provisions (eg, the Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994, Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights 1996, Health Information Privacy Code 2020, Privacy Act 1993 and Privacy Amendment Act 2013).

Providing meaningful information to enable an informed choice and to seek informed consent is a duty that all health and disability providers must meet to uphold the rights of health and disability consumers. Informed consent includes the right to be honestly and openly informed about one’s personal health matters. The right to agree to treatment carries with it the right to refuse and withdraw from treatment.

Informed consent is also an external expression of a health care provider’s pivotal ethical duty to uphold and enhance their patient’s autonomy by respecting the patient’s personhood in every aspect of their relationship with that individual.

The informed consent process

Informed consent is a process whereby the individual or parent/guardian are appropriately informed in an environment and manner that are meaningful. Having been well informed, they are willing and able to agree to what is being suggested without coercion.

Regardless of age, an individual and/or their parent/guardian must be able to understand:

- that they have a choice

- why they are being offered the treatment/procedure

- what is involved in what they are being offered

- the probable benefits, risks, side-effects, failure rates and alternatives, and the risks and benefits of not receiving the treatment or procedure.

To make an informed choice and give informed consent for vaccination, the individual or parent/guardian needs to understand the benefits and risks of vaccination, including those to the child and community.

Consent for patients who are incompetent (individuals who do not have the capacity to consent) may be given by:

- a welfare guardian appointed under the Protection of Personal and Property Rights Act 1988

- an attorney under an activated enduring power of attorney in respect of care and welfare.

If there is no welfare guardian or attorney under an enduring power of attorney, treatment may be provided under Right 7(4) of the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights if:

- the treatment is in the best interests of the patient; and

- attempts have been made to find out what the patient would have wanted if s/he were competent; or

- if it is not possible to find out what the patient would have wanted, the views of people interested in the patient’s welfare have been considered.

The essential elements of the informed consent process are effective communication, full information and freely given competent consent. The specific rights in the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights that represent these three elements are:

- Right 5: Right to effective communication

- Right 6: Right to be fully informed

- Right 7: Right to make an informed choice and give informed consent.[1]

For example, section 7(1) of the Code states that ‘services may be provided to a consumer only if that consumer makes an informed choice and gives informed consent, except where any enactment, or the common law, or any other provision of the Code provides otherwise.’ Information on the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights can be found on the Health and Disability Commissioner’s website.

Health professionals have legal obligations to obtain informed consent prior to a procedure and prior to data collection (eg, data collected for the AIR). Unless there are specific legal exceptions to the need for consent, the health professional who acts without consent potentially faces the prospect of a civil claim for exemplary damages, criminal prosecution for assault (sections 190 and 196 of the Crimes Act 1961), complaints to the Health and Disability Commissioner and professional disciplining.

Ensuring that an individual has made an informed choice regarding treatment options has been included in the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003. This Act ensures that health practitioners are, and remain, competent and safe to practise. For example, the Nursing Council of New Zealand competencies for the Registered Nurse Scope of Practice, Competency 2.4, ‘ensures the client has adequate explanation of the effects, consequences and alternatives of proposed treatment options’ (see the Nursing Council of New Zealand website).

Privacy and control over personal information

The right to authorise, or to exert some control over, the collection and disclosure of personal information about oneself is a right closely allied to that of consent to treatment and is also relevant to personal integrity and autonomy.

The Health Information Privacy Code 2020 requires health agencies collecting identifiable information to be open about how and for what purpose that information will be used and who will be able to see it (Rule 3).

In addition to providing information about collection by the vaccinating agency, people should be advised that vaccination information will be recorded in the Aotearoa Immunisation Register (AIR) maintained by Health New Zealand and directed to the online privacy statement for the AIR on the Health NZ website. This includes information on their choices with respect to control over their information.

The Health Information Privacy Code 2020 also gives people the right to access, and seek correction of, health information about them (Rules 6 and 7). Parents and guardians have a similar right of access to information about their children.

Further information about privacy and health information can be found on the Privacy Commissioner’s website.

Immunisation consent in primary care

Parents should be prepared during the antenatal period for the choice they will have to make about their child’s vaccination. During the third trimester of pregnancy, the lead maternity carer must provide Ministry of Health information on immunisation and the AIR. This is a requirement under clause DA21(c) of the Primary Maternity Services Notice 2007, pursuant to section 88 of the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000.

Vaccine hesitancy

"Vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, place and vaccines. It includes factors such as complacency, convenience and confidence."

- WHO: Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy

Effective communication and active listening are key components of the informed consent process, especially when health care providers are working with vaccine-hesitant individuals/parents/guardians. In this situation, providers should:

- be willing to initiate the conversation, and avoid leaving it to others

- tailor content to the needs of the individual

- ensure respect and acknowledgement of concerns

- use plain language, open-ended questions and active listening

- avoid medical jargon, or ensure it is explained

- offer resources

- finish with an effective immunisation recommendation.

Information for parents, guardians and health care providers

Health care providers must offer information without individuals or parents/guardians having to ask for it. The depth of information offered or required may differ, but it should at least ensure that the individual or parent/guardian understands what the vaccine is for and the possible side-effects, as well as information about the vaccination programme, the AIR and the risks of not being vaccinated (see chapter 3).

Every effort should be made to ensure that the need for information is met, including extra discussion time, use of an interpreter and alternative-language pamphlets. Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora immunisation pamphlets are produced in several languages, and are available from the local authorised provider or can be ordered, viewed and/or downloaded from the HealthEd website.

Issues to discuss with individuals or parents/guardians about immunisation include:

- the vaccine-preventable diseases

- the vaccines used on the Schedule (ie, the funded vaccines that are available)

- how vaccines work, known risks and adverse events, and what the vaccine is made of, in case of known allergies

- the collection of immunisation information on the AIR from birth, or as part of a targeted immunisation programme (eg, the information that will be collected, who will have access to it and how it will be used; see section 2.3.5 for more information on the AIR)

- the choice to vaccinate.

Informed consent is required for each immunisation episode or dose. Presentation for an immunisation event should not be interpreted as implying consent. Individuals and parents/guardians have the right to change their mind at any time. Where consent is obtained formally but not in writing, the provider should document what was discussed, and that consent was obtained and by whom.

Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora information

Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora immunisation information is available for parents and guardians on the Health New Zealand website. Parents and guardians may also order, view or download Health New Zealand immunisation information from the HealthEd website or from the local authorised resource provider, including:

- Immunise Your Child on Time (leaflet, available in English [HE1327] and other languages)

- Childhood Immunisation (health education booklet [HE1323]).

Further immunisation consent information for health care providers is also available in Appendix 3 ‘Immunisation standards for vaccinators and guidelines for organisations offering immunisation services’. Responses to commonly asked questions and suggestions for addressing myths and concerns are available in chapter 3.

Other information sources

- Sharing Knowledge About Immunisation (SKAI) is an Australian suite of online resources and tools to support vaccination communication designed to aid conversations about childhood immunisation for parents and health care providers.

- Offit PA, Moser C. 2011. Vaccines and Your Child – Separating fact from fiction. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Vaccine manufacturers’ data sheets, available on the Medsafe website. Consumer and health care provider versions are available.

- Other recommended immunisation-related websites (see Appendix 8).

Alternatively, contact:

- the Immunisation Advisory Centre on freephone 0800 IMMUNE/0800 466 863, or see the IMAC website

- your local immunisation coordinator (a list of regional contacts are available on the IMAC website).

Immunisation consent in other settings (eg, schools)

In mass immunisation campaigns, such as those undertaken at schools, the consent requirements are different from those that apply to the vaccination of individuals in primary care. The parent/guardian may not be with the child on the day of immunisation, so immunisation should proceed only after the parent/guardian has had the opportunity to read the immunisation information and discuss any areas of concern. Consent forms are provided for immunisations given in schools by public health nurses and may also be used in mass vaccination settings. For children aged under 16 years who are being immunised at school, written consent must be obtained from the parent/guardian. Individuals who are aged 16 years or older may self-consent.

Consent and children

Under the Code of Rights, every consumer, including a child, has the right to the information they need to make an informed choice or to give informed consent. The law relating to the ability of children to consent to medical treatment is complex. There is no defined age at which all children can consent to all health and disability services. The presumption that parental consent is necessary to give health care to those aged under 16 years is inconsistent with common law developments and the Code of Rights.

The Code of Rights makes a presumption of competence (to give consent) in relation to children, although New Zealand is unusual in this respect (ie, the obligations regarding consent of minors are greater in New Zealand than in many other jurisdictions).

A child aged under 16 years has the right to give consent for minor treatment, including immunisation, providing he or she understands fully the benefits and risks involved. In 2002 the Health and Disability Commissioner provided an opinion of a child’s consent to a vaccine, whereby the Commissioner was satisfied that a 14-year-old was competent to give informed consent for an immunisation event due to an injury where a tetanus toxoid vaccine would be commonly given. More details of this opinion can be found on the Health and Disability Commissioner’s website (Case: 01HDC02915).

Further information on informed consent can be found on the Health and Disability Commissioner’s website.

2.1.3. Pre-vaccination screening

2.1.3. Pre-vaccination screening

Prior to immunisation with any vaccine, the vaccinator should ascertain if the vaccine recipient (child or adult) has a condition or circumstance which may influence whether a vaccine is given, deferred or contraindicated. Table 2.2 below provides a checklist of conditions or circumstances to screen for, along with the appropriate action to take and a rationale.

The vaccinator will also need to determine which vaccines are due, assess the vaccine recipient’s overall current vaccination status and address parental concerns. The vaccinator also needs to advise the individual/parent/guardian they will need to remain for 20 minutes post-vaccination.

Table 2.2: Pre-vaccination screening and actions to take

Table 2.2: Pre-vaccination screening and actions to take

|

Condition* or circumstance |

Action |

Rationale |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Is unwell today:

|

Defer all vaccines until afebrile. Note: Children with minor illnesses (without acute symptoms/signs) should be vaccinated. |

To avoid an adverse event in an already unwell child, or to avoid attributing symptoms to vaccination. |

|

|

Is a preterm infant and had apnoea following immunisation in hospital (at 6-week and/or 3-month event) |

Re-admission for the next infant immunisation and respiratory monitoring for 48 to 72 hours may be warranted,[2] but do not avoid or delay immunisation. Babies born <28 weeks’ gestation and other preterm babies who develop chronic lung disease will require PCV13 plus 23PPV at 2 years (see section 4.2.2). |

There is a potential risk of apnoea in infants born before 28 weeks’ gestation. Preterm infants may be at increased risk of vaccine-preventable diseases (eg, invasive pneumococcal disease). |

|

|

Previously had a severe reaction to any vaccine |

Careful consideration will be needed depending on the nature of the reaction. If in doubt about the safety of future doses, seek specialist advice. |

Anaphylaxis to a previous vaccine dose or any component of the vaccine is an absolute contraindication to further vaccination with that vaccine. |

|

|

Anaphylaxis to vaccine components (eg, gelatin, neomycin) |

Refer to the relevant vaccine data sheet for the components. If an individual has had anaphylaxis to any component contained in a vaccine, seek specialist advice. Note: Egg allergy, including anaphylactic egg allergy, is not a contraindication to MMR or influenza vaccination (see sections 11.6.3 and 12.6.3). |

Vaccinators need to be aware of the possibility that allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, may occur after any vaccination without any apparent risk factors (see section 2.3.3). Delayed hypersensitivity to a prior vaccine dose or a component of a vaccine is not a contraindication to further doses, but it is important to distinguish this from anaphylaxis. |

|

|

Appropriate spacing between doses of the same vaccine (when was the last vaccination, and what was it?) |

See section 2.1.5 and check the relevant disease chapters and catch-up schedules. (See below for live parenteral vaccines.) |

The general rule is for a minimum of 4 weeks between doses of a primary series and 4 months between the priming dose(s) and the booster. |

|

|

Had a live parenteral vaccine within the last 4 weeks – if in doubt, check the individual’s immunisation status on the AIR |

Delay further live attenuated parenteral vaccines to 4 weeks. Note that this does not apply to rotavirus vaccine, which is an oral vaccine. |

The antibody response to the first dose may interfere with the response to the second. They may be given on the same day. |

|

|

Had an injection of immunoglobulin or a blood transfusion within the last year and is now due for a live vaccine |

Check which product the person received and the interval since administration. See Table A6.1. Delay vaccination if necessary. |

Live virus vaccines should be given at least 2 weeks before or deferred. The interval will be determined by the blood product and dose received. |

|

|

Has a disease that lowers immunity, is receiving treatment that lowers immunity or is an infant of a mother who received immunosuppressive therapy during pregnancy |

See chapter 4 ‘Immunisation of special groups’. In some cases, specialist advice may need to be sought before vaccination. Note: Persons living with someone with lowered immunity should be fully vaccinated, including with live viral vaccines (see section 4.3.1). |

The safety and effectiveness of the vaccine may be suboptimal in persons who are immunocompromised. Live attenuated vaccines may be contraindicated. |

|

|

Is planning a pregnancy |

See section 4.1.1 ‘Women planning pregnancy’. Ensure women and household members have received all vaccines recommended for their age group. Women should know if they are immune to measles (section 12.8.3), rubella (section 21.5.3) and varicella (section 24.5.4). Advise women not to become pregnant within 4 weeks of receiving live viral vaccines. |

Vaccinating before pregnancy may prevent maternal illness, which could affect the infant, and may confer passive immunity to the newborn. |

|

|

Is pregnant |

See sections 4.1.2 ‘During pregnancy’ and 4.1.3 ‘Breastfeeding and post-partum’. COVID-19, influenza and Tdap vaccines are recommended. |

Vaccinating (with inactivated or subunit vaccines) during pregnancy may prevent maternal illness, which could affect the infant, and confers passive immunity to the newborn. |

|

|

Live vaccines should be avoided until after the delivery. |

Deferring administration of live vaccines until after delivery is a precautionary safety measure. Studies of women who inadvertently received a live vaccine during pregnancy and their infants have not identified any adverse effects. |

||

|

Unstable neurological condition (for pertussis-containing vaccines only) |

Seek specialist advice. |

Vaccination is recommended for children with unstable neurological conditions as they may be at high risk of severe pertussis complications. Individual cases should be discussed with a specialist. |

|

|

Thrombocytopenia or bleeding disorders |

Administer intramuscular vaccines with caution:

|

A haematoma may occur following intramuscular administration. In some cases, subcutaneous is preferred where datasheet allows. Seek specialist advice as appropriate. |

|

|

Individuals who are currently being treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, as well as those who have discontinued treatment within the past 6 months. |

Contraindication for live vaccines. |

There is a theoretical risk that vaccines may trigger an autoimmune response in these individuals. See the ‘Immune checkpoint inhibitor (immunostimulant) therapy’ discussion in section 4.3.8. |

|

| History of myocarditis or pericarditis |

If unrelated to vaccination, continue vaccination (for COVID-19 and mpox vaccines, continue once cardiac inflammation has resolved). |

To reduce potential risk of exacerbating underlying condition |

|

| Defer further doses if individual develops myocarditis/pericarditis after any dose of mRNA-CV or rCV. Seek specialist immunisation advice regarding future COVID-19 vaccination doses. | To consider risk of recurrent myocarditis/pericarditis against risk of severe COVID-19 | ||

|

Any further doses of MPV (mpox) vaccine are contraindicated if myocarditis or pericarditis is considered related to a previous dose. |

|||

|

History of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) |

The risks and benefits of withholding vaccination should be considered on an individual basis. |

Consider the risk of recurrent GBS following influenza infection. |

|

|

* See chapter 4 for more information about pregnancy and lactation and for information about infants with special immunisation considerations, immune-deficient and immunosuppressed individuals, immigrants and refugees, travel, and occupational and other risk factors. Adapted from: Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). 2018. Australian Immunisation Handbook. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health (accessed 30 June 2020). |

|||

2.1.4. Contraindications

2.1.4. Contraindications

No individual should be denied vaccination without serious consideration of the consequences, both for the individual and for the community. Where there is any doubt, seek advice from the individual’s general practitioner (GP), a public health medicine specialist, medical officer of health, consultant paediatrician or IMAC.

Anaphylaxis to a previous vaccine dose or any component of the vaccine is an absolute contraindication to further vaccination with that vaccine. (Note that egg-related anaphylaxis and influenza vaccine or MMR are exceptions.)

For more detail on anaphylaxis, see section 2.3.3.

Live viral vaccines should not be given to pregnant women, nor, in general, to immunosuppressed individuals and those treated within the last 6 months with immune checkpoint inhibitors (see chapter 4).

See the relevant disease chapter section for more specific vaccine contraindications.

Conditions that are not contraindications to immunisation

The conditions in Table 2.3 are not contraindications to the immunisation of children and adults (see also section 3.1).

Table 2.3: Conditions that are not contraindications to immunisation

Individuals with these conditions should be vaccinated with all the recommended vaccines.

|

Mildly unwell, with a temperature ≤38°C |

|

Asthma, hay fever, eczema, ‘snuffles’, allergy to house dust |

|

Receiving treatment with antibiotics or locally acting steroids |

|

A breastfeeding mother or a breastfed child |

|

Neonatal jaundice |

|

Low weight in an otherwise healthy child |

|

The child being over the usual age for immunisation – use age-appropriate vaccines, as per the catch-up schedules in Appendix 2 (the exception is rotavirus vaccine: see section 20.5.2) |

|

A previous hypotonic-hyporesponsive episode (see section 2.3.3) |

|

Clinical history of pertussis, measles, mumps or rubella infection – clinical history without laboratory confirmation cannot be taken as proof of immunity (even when an individual is proven to be immune to one or two of either measles, mumps or rubella, there is still the need for immunisation against the other/s: see relevant chapters) |

|

Prematurity, but an otherwise well infant – it is particularly important to immunise these children, who are at higher risk of severe illness if infected; immunisation is recommended at the usual chronological age (see ‘Preterm and low birthweight infants’ in section 4.2.2) |

|

Stable neurological conditions, such as cerebral palsy or Down syndrome |

|

Contact with an infectious disease |

|

Egg allergy, including anaphylaxis, is not a contraindication to MMR (see section 12.6.3) or influenza vaccine (see section 11.6.3) |

|

Family history of vaccine reactions |

|

Family history of seizures |

|

Family history of sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI) |

|

Child’s mother or household member is pregnant or immunocompromised |

2.1.5. Spacing of doses

2.1.5. Spacing of doses

In general, follow the recommendations in the manufacturers’ data sheets.

Principles for spacing of doses of the same vaccine

The immune response to a series of vaccines depends on the time interval between doses. The general rule is for a minimum of four weeks between doses of a primary series; however, the immune response may be better with longer intervals. A repeat dose of the same vaccine given less than four weeks after the previous dose may result in a reduced immune response. Specific recommendations for a rapid schedule by the manufacturer may apply for some vaccines.

Generally, a minimum interval of four to six months between priming dose(s) and the booster dose allows affinity maturation of memory B cells, and thus higher secondary responses (see section 1.1).

It is not necessary to repeat a prior dose if the time elapsed between doses is more than the recommended interval.

Spacing of different vaccines

Two or more parenterally administered live vaccines may be given at the same visit; for example, MMR and VV. However, when given at different visits, a minimum interval of four weeks is recommended. This interval is to avoid the response to the second vaccine being diminished due to interference from the response to the first vaccine.

Note that no interval is required between administration of Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) and rotavirus vaccines.

Unless there is a specific recommendation against it, a subunit vaccine can be administered either simultaneously or at any time before or after a different subunit or live vaccine.

Concurrent administration of vaccines

Changing the timing of visits or increasing the number of visits to avoid multiple injections delays protection against potentially serious diseases and may also lead to incomplete immunisation. Best practice is to follow the Schedule.

Where different injectable vaccines are given on the same day, they must be administered in separate syringes, at different sites.

2.1.6. Catch-up programmes for unimmunised or partially immunised children

2.1.6. Catch-up programmes for unimmunised or partially immunised children

The objective of a catch-up programme is to complete a course of vaccinations that provides adequate protection. Catch-up programmes should be based on documented evidence of previous vaccination (eg, the child’s Well Child Tamariki Ora My Health Book, AIR, or overseas immunisation records).

When children have missed vaccine doses, it is important to bring them up to date as quickly as possible. Where more than one vaccine is overdue, it is preferable to give as many as possible at the first visit. For children aged 12 months and older, MMR is the priority.

See Appendix 2 for determining catch-up requirements and planning a catch-up programme.

If the vaccinator is uncertain about how to plan a catch-up programme, they should contact the local immunisation coordinator, IMAC, medical officer of health or public health service.

Once catch-up is achieved, vaccination for the child should continue as per the Schedule.

Vaccination of children with inadequate vaccination records

It is recommended that children without a documented history of vaccination have a full course of vaccinations appropriate for their age. It is preferable, and safe, for the individual to receive an unnecessary dose rather than to miss out a required dose(s) and not be fully protected.

2.1.7. Adult vaccination (aged 18 years and older)

2.1.7. Adult vaccination (aged 18 years and older)

Whenever adults are seen in general practice or by immunisation providers, there is an opportunity to ensure they have been adequately protected against the following diseases and have received at least a primary immunisation course as described in Table 2.4. If the requisite number of doses has not been received, catch-up vaccination is recommended and funded (see Appendix 2).

Women of childbearing age should know whether or not they are immune to measles (see chapter 12), rubella (see chapter 21) and varicella (see chapter 24).

Refer to the PHARMAC schedule for further details on vaccines funded for adults (available on the PHARMAC website).

Table 2.4: Funded immunisation for adults

Table 2.4: Funded immunisation for adults

|

Vaccine |

Number of vaccine doses |

|---|---|

|

Tdap |

3 dosesa |

|

Poliomyelitis (IPV) |

3 doses |

|

Measles, mumps, rubella |

2 doses |

|

HPV (aged 26 years and under) |

3 dosesb |

|

Influenza |

1 dose annually (for eligible groups) |

| COVID-19 (mRNA-CV) | 2 dosesc (additional doses for eligible groups) |

| Zoster (rZV, at age 65 years) |

2 doses |

|

a. Although pertussis protection is included in the Tdap vaccine as part of protection against Tetanus and diphtheria, if a patient is missing this antigen only but is otherwise fully vaccinated, no further vaccines are required unless the patient is pregnant. b. Individuals who were under age 27 years when they commenced HPV vaccination are currently funded to complete the 3-dose course, even if they are older than 27 years when they complete it. c. Includes all adults, regardless of eligibility to health and disability services. One other COVID-19 vaccine is available (see section 5.4.2). |

|

See Table 2.5 below for additional adult vaccination recommendations, including vaccinations recommended for special groups (funded vaccines are in the shaded boxes). See also chapter 4 ‘Immunisation of special groups’ for information about immunisation during pregnancy and lactation (section 4.1), of immunocompromised individuals (section 4.3), of immigrants and refugees (section 4.7), for those with occupational-related vaccination (section 4.8) and for travel (section 4.9).

Table 2.5: Adult (≥18 years) vaccination recommendations, excluding travel requirements

Table 2.5: Adult (≥18 years) vaccination recommendations, excluding travel requirements

|

Vaccine |

Recommended and funded |

Recommended but not funded |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 (chapter 5) |

All adults Three primary doses for severely immunocompromised Additional doses available |

||

|

(Re)vaccination of patients post-haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) or chemotherapy; pre- or post-splenectomy or with functional asplenia; pre- or post-solid organ transplant, pre- or post-cochlear implants, renal dialysis and other severely immunosuppressive regimens |

|

||

|

Hepatitis A |

Transplant patients Close contacts of hepatitis A casesa |

Patients with chronic hepatitis B or C infection; men who have sex with men; adults at occupational risk |

|

|

Hepatitis B |

Household or sexual contacts of patients with acute or chronic HBV infection HIV-positive patients Hepatitis C-positive patients Following non-consensual sexual intercourse Prior to or following immunosuppressionb Solid organ transplant patients Post-HSCT patients Following needle-stick injury Dialysis patients Liver or kidney transplant patients |

Non-immune adults at risk including occupational or other risk factors |

|

|

HPV |

All individuals aged 9–26 yearsc,d Individuals aged 18–26 years who are:c,d

|

Adults ≥27 years:c,d,e

|

|

|

Annual influenza vaccine |

Pregnant women and people Individuals aged 65 years and older Individuals aged under 65 years with eligible conditions |

Close contacts of elderly adults and other high-risk groups All other adults |

|

|

Any individual susceptible to any one of these three diseases (Re)vaccination prior to planned or following immunosuppressionb |

|

||

|

For patients who are pre- or post-splenectomy or with functional asplenia; with HIV; with complement deficiency (acquired, including monoclonal antibody therapy against C5, or inherited); who are pre- or post-solid organ transplant Close contacts of meningococcal casesa Patients who have had previous meningococcal disease (any group) HSCT (bone marrow transplant) patients Patients prior to planned and following immunosuppressionb Adolescents and young adults aged 13–25 years inclusively who will be living or are currently living in a boarding school hostel or university hall of residence, military barracks, youth justice residences or prison |

Laboratory workers handling bacterial cultures Health care professionals in very close contact with cases |

||

|

Tdap is recommended to be given from 16 weeks’ gestation of every pregnancy, preferably in the second trimester to protect both the mother and her infant from pertussis Tdap for (re)vaccination of patients who are post-HSCT or chemotherapy; pre- or post-splenectomy; pre- or post-solid organ transplant, renal dialysis and other severely immunosuppressive regimens |

Tdap if in contact with infants aged under 12 months |

||

|

(Re)vaccination of patients with HIV; pre- or post-HSCTf or chemotherapy;f pre- or post-splenectomy or with functional asplenia; pre- or post-solid organ transplant; renal dialysis; complement deficiency (acquired or inherited); cochlear implants; primary immune deficiency |

PCV13 followed by 23PPV for those with certain conditions PCV13 followed by 23PPV for those aged 65 years or older |

||

|

IPV |

Any unvaccinated or partially vaccinated individual (Re)vaccination prior to planned or following immunosuppressionb |

Travellers to certain high-risk countries |

|

|

Tdap for susceptible individuals (including following immunosuppression); boosters at 45 (if had less than 4 previous doses of tetanus vaccine) plus 65 years; boosting of patients with tetanus-prone wounds |

|

||

|

Varicella |

Non-immune patients:

Patients at least 2 years after bone marrow transplantg Patients at least 6 months after completion of chemotherapyg HIV-positive patients who are non-immune to varicella, with mild or moderate immunosuppressiong Patients with inborn errors of metabolism at risk of major metabolic decompensation, with no clinical history of varicella Household members of paediatric patients who are immunocompromised or undergoing a procedure leading to immunocompromise, where the household member has no clinical history of varicella Household members of adult patients who have no clinical history of varicella and who are severely immunocompromised or undergoing a procedure leading to immunocompromise, where the household member has no clinical history of varicella |

Susceptible adults |

|

|

Zoster |

Individuals at age 65 years. Individuals aged from 18 years, including those aged 66 years and over,

|

rZV may be considered, but is not funded, for individuals who are:

|

|

|

a. Only 1 dose of vaccine is funded for close contacts. b. Note that the period of immunosuppression due to steroid or other immunosuppressive therapy must be longer than 28 days. c. Individuals who started with HPV4 may complete their remaining doses with HPV9. d. Individuals who were <27 years when they commenced HPV vaccination are currently funded to complete the 3-dose course, even if they are ≥27 years when they complete it. e. HPV9 vaccine is registered for use in females and males aged 9–45 years. f. PCV13 is funded pre- or post-HSCT or chemotherapy. 23PPV is only funded post-HSCT or chemotherapy. g. On the advice of their specialist. h. Available for use for certain medical conditions from age 18 years. |

|||

2.2. Vaccine administration

2.2.1. Minimising pain and distress at the time of vaccination

2.2.1. Minimising pain and distress at the time of vaccination

The WHO key recommendations for minimising pain and distress at the time of vaccination are:[3, 4]

- do not aspirate (draw back) when giving vaccines

- administer vaccines from the least to the most painful for all ages

- breastfeed before and during vaccine injection

- position (hold the infant/young child, individuals aged 3 years and older should sit up, parental presence)

- for infants, give oral rotavirus vaccine before injections (the vaccine contains sucrose that can reduce pain)

- use calming and supportive words at the time of vaccination; avoid language that increases anxiety

- provide appropriate distractions

- consider using topical anaesthetics (only if the cost is acceptable to the family).

See also section 2.3.2 and the IMAC factsheets Mitigating Vaccination Pain and Distress and Fear of Needles or Needle Phobia (available on the IMAC website).

2.2.2. Preparing for vaccine administration

2.2.2. Preparing for vaccine administration

Key points for administering injectable vaccines

Vaccines should not be mixed in the same syringe, unless the prescribing information sheet specifically states it is permitted or essential (eg, DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib).

Careful use of a longer needle will cause less damage than a short needle.

To avoid tracking, make sure all the vaccine has been injected before smoothly withdrawing the needle.

Correct vaccine administration is important, and vaccinators have a responsibility to see that vaccines are given:

- in the optimal site as recommended in Handbook

- using the appropriate needle size for vaccine effectiveness and patient safety.

The use of alternative sites will be based on professional judgement, including knowledge of the potential risks at each site and recommendations in the manufacturer’s data sheet.

The guidelines in Table 2.6 will help to make the experience less distressing for the individual, parent/guardian and/or whānau, and vaccinator.

Table 2.6: Guidelines for vaccine administration

|

Preparation |

Immunisation event |

|---|---|

|

Vaccinate in a private and appropriate setting. |

Draw up injections out of sight, if possible. Medical equipment is commonplace to vaccinators, but it may heighten the anxiety of some individuals. |

|

Prepare the area/room layout to suit the vaccinator and vaccination event. |

Ensure the individual or parent/guardian has had the opportunity to discuss any concerns and has given informed consent. |

|

Be familiar with the vaccines (eg, their correct preparation, administration and the potential for adverse events). |

Be prepared to include other family members and whānau in the discussion; explain to older children accompanying infants why the injections are being given and what will happen. |

|

Be aware of the individual’s immunisation history (eg, submit a status query to the AIR, if the history is unknown). |

Give the appropriate immunisations due and advise when the next immunisation event is due. |

|

Ensure there are age-appropriate distractions available. |

For breastfed babies, suggest that the mother breastfeeds baby before, during and after immunisation. For children, sit them upright and talk quietly to them before and during immunisation. Make eye contact and explain what is going to happen. Even when a child is unable to understand the words, an unhurried, quiet approach has a calming effect and reassures the parent/guardian. See also section 2.3.2. |

|

Ensure the relevant immunisation health education resources are available. |

Give written and verbal advice to the individual and parent/guardian. The advice should cover what may be expected after immunisation, and what to do in the event of an adverse event, along with advice on when to notify the vaccinator. |

Removal of air bubbles

Advice for removal of air in the syringe before vaccine administration is dependent on the vaccine presentation. For guidelines see Table 2.7.

Table 2.7: Guidelines for management of air bubbles in a vaccine syringe

|

Vaccine presentation |

Management of air bubbles |

|---|---|

|

Vaccines supplied in a prefilled syringe with a fixed needle |

Do not expel the air |

|

Vaccines supplied in a prefilled syringe without a fixed needle (eg, Gardasil 9) |

Add an appropriate administration needle Do not expel the air |

|

Vaccines supplied diluted in a vial |

Draw up the entire vaccine volume into a syringe Expel the air until the vaccine is at the level of the syringe hub, then change the needle Do not expel the air contained in the new needle |

|

Vaccines supplied as diluent and powder/pellet requiring reconstitutiona |

Reconstitute the vaccine correctly Draw up the entire vaccine volume into a syringe Expel the air until the vaccine is at the level of the syringe hub, then change the needlea Do not expel the air contained in the new needle |

|

a. See section 5.4.5 for administration procedures of COVID-19 vaccines. |

|

Skin preparation

Skin preparation or cleansing when the injection site is clean is not necessary. However, if an alcohol swab is used, it must be allowed to dry for at least two minutes, otherwise alcohol may be tracked into the muscle, causing local irritation. Alcohol may also inactivate a live attenuated vaccine such as MMR.

A dirty injection site may be washed with soap and water and thoroughly dried before the immunisation event.

Special considerations for COVID-19

In patients who have had acute COVID-19 illness or tested positive for SARS-CoV2 virus, COVID-19 vaccination is recommended to be continued from six months after recovery from acute illness, or six months from the first confirmed positive test if asymptomatic. This applies for any additional doses (see Vaccination following SARS-CoV-2 infection) For all other vaccines, commence vaccination as soon as the individual is no longer acutely unwell and when cleared to leave isolation.

2.2.3. Route of administration

2.2.3. Route of administration

Most Schedule vaccines are administered by intramuscular injection. The exceptions are IPV (IPOL; subcutaneously), BCG (intradermally) and rotavirus (oral). Live vaccines have previously been given via SC route and data sheets may still show this as an option, which can be helpful for those with bleeding disorders (see below).

Needle angle, gauge and length

Intramuscular injections should be administered at a 90-degree angle to the skin plane. The needle length used will be determined by the size of the limb and muscle bulk, whether the tissue is bunched or stretched and the vaccinator’s professional judgement. BCG vaccine (which can only be administered by authorised vaccinators with BCG endorsement) is given by intradermal injection. See Table 2.8.

Table 2.8: Needle gauge and length, by site and age

|

Age |

Site |

Needle gauge and length |

Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Intramuscular (IM) injection |

|||

|

Birth |

Vastus lateralis |

23–25 G × 16 mm |

|

|

6 weeks |

Vastus lateralis |

23–25 G × 16 or 25 mm |

Choice of needle length will be based on the vaccinator’s professional judgement. |

|

3–11 months |

Vastus lateralis |

23–25 G × 25 mm |

A 25 mm needle will ensure deep IM vaccine deposition. |

|

12 months to |

Deltoid or Vastus lateralis |

23–25 G × 16 mm

23–25 G × 25 mm |

The vastus lateralis site may be the preferred option in young children if deltoid muscle bulk is small or multiple injections are necessary. |

|

3–7 years |

Deltoid or Vastus lateralisa |

23–25 G × 16 mm

21–22 G × 25 mm |

A 16 mm needle should be sufficient to effect deep IM deposition in the deltoid in most children. |

|

Older children (7 years and older), adolescents and adults |

Deltoid

Vastus lateralisa |

23–25 G × 16 mm, or

21–22 G × 38 mm |

Most adolescents and adults will require a 25 mm needle to effect deep IM deposition. |

|

Very large or obese person |

Deltoid |

21-22 G x 38 mm |

Use clinical judgment to ensure needle length is appropriate to reach muscle.[4,5] |

|

Subcutaneous injection |

|||

|

Subcutaneous injection |

Deltoid region of the upper arm |

25–26 G × 16 mm |

An insertion angle of 45 degrees is recommended. The needle should never be longer than 16 mm or inadvertent IM administration could result. |

|

Intradermal injection: BCG vaccine – for authorised vaccinators with BCG endorsement |

|||

|

Intradermal injection |

Slightly above the insertion of the deltoid muscle on the lateral surface of the left arm. The arm should be gently but firmly supported. |

Drawing-up: Tuberculin syringe (attach a drawing-up needle), or a single-use insulin syringe with a needle attached

|

|

|

Administering: If using a tuberculin syringe, change the needle to a sterile 26 G × 13 or 16 mm needle (no needle change required if using an insulin syringe) |

The syringe should be held with the bevel uppermost, parallel with the skin of the arm. The bevel should be fully inserted but visible under the skin. Inject the vaccine slowly and gradually to form a white ‘bleb’ or wheal, then gradually withdraw the needle. |

||

| a. Consideration may be given to the vastus lateralis as an alternative vaccination site, providing it is not contraindicated by the manufacturer’s data sheet. | |||

Intramuscular injection sites

Injectable vaccines should be administered in healthy, well-developed muscle, in a site as free as possible from the risk of local, neural, vascular and tissue injury. Incorrectly administered vaccines (incorrect sites and poor administration techniques) contribute to vaccine failure, injection-site nodules or sterile abscesses, and increased local reactions.

Careful use of a longer needle will cause less damage than a shorter needle.

The recommended sites for intramuscular (IM) vaccines (based on proven uptake and safety data) are:

- the vastus lateralis muscle on the anterolateral thigh for infants aged under 12 months – the vastus lateralis muscle is large, thick and well developed in infants, wrapping slightly onto the anterior thigh

- either the vastus lateralis or deltoid site for children aged 12 months to 3 years (see below)

- the deltoid muscle for older children, adolescents and adults.

The deltoid muscle is not routinely used in infants and young children aged under 12 months, due to the potential for deltoid or radial nerve injury. However, when there is no access to the vastus lateralis (eg, the infant is in a spica cast), the deltoid muscle is used to administer intramuscular vaccines.

The buttock should not be used for the administration of vaccines in infants or young children, because the buttock region is mostly subcutaneous fat until the child has been walking for at least 9 to 12 months. Use of the buttock is not recommended for adult vaccinations either, because the buttock subcutaneous layer can vary from 1 to 9 cm and IM deposition may not occur.

With older children and adults, consideration may be given to using the vastus lateralis as an alternative site to the deltoid.

Subcutaneous injection sites

A subcutaneous (SC) injection should be given into healthy tissue that is away from bony prominences and free of large blood vessels or nerves. The recommended site for subcutaneous vaccine administration is the upper arm (overlying the deltoid muscle).

The principles for locating the upper arm site for an SC injection are the same as for an IM injection. However, needle length is more critical than angle of insertion for subcutaneous injections. An insertion angle of 45 degrees is recommended, and the needle should never be longer than 16 mm, or inadvertent IM administration could result. The thigh may be used for SC vaccination unless contraindicated by the manufacturer’s data sheet. For patients with thrombocytopenia and bleeding disorders, the risk of haematoma may be reduced when given via SC route. See below for further details.

Intramuscular versus subcutaneous administration

Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora recommends that parenteral live vaccines on the Schedule (MMR and varicella vaccines) be administered via intramuscular (IM) route, unless the patient is on an anticoagulant or has a bleeding disorder, in which case the preferred route is subcutaneous (SC) where the data sheet allows (see below). Historically, live vaccines have been given subcutaneously following on from their original licensure trials. Further research has now established immunogenicity and safety when these vaccines are administered by the IM route.[6] There is evidence that injections given intramuscularly, rather than deep subcutaneously, are less likely to cause local reactions.[8, 9, 10] There are no immunogenicity concerns when MMR and varicella vaccines are given either SC or IM. BCG is required to be given intradermally.

Thrombocytopenia, anticoagulant therapy and bleeding disorders

For patients with thrombocytopenia and bleeding disorders, the risk of haematoma may be reduced when given via SC route, where data sheet allows this option.

- Vaccines can be administered to people on anticoagulants, dabigatran (Pradaxa), enoxaparin (Clexane), heparin, ticagrelor (Brilinta) and warfarin. Subcutaneous route is preferred option where data allows, to reduce risk of haematoma. For vaccines that do not have the SC option administer IM. After vaccination, apply firm pressure over the injection site without rubbing for 10 minutes to reduce the risk of bruising.

- For patients with haemophilia receiving clotting factor replacement or a similar therapy, vaccinations should be given as soon as possible after receiving the medicine and vaccines should be given in the same way as for those on anticoagulants. Specialist advice is recommended.

Intradermal injections

The intradermal injection technique for BCG vaccine (see section 2.2.4) requires special training, and should only be performed by an authorised vaccinator with BCG endorsement (see A3.6).

Oral vaccine administration

The rotavirus vaccine is administered orally. Administer the entire contents of the oral applicator into the infant’s mouth, towards the inner cheek (see section A7.2.4). Do not inject oral vaccines.

For specific oral vaccine administration instructions, refer to the vaccine data sheet (available on the Medsafe website).

2.2.4. Infant vaccination

2.2.4. Infant vaccination

Infants aged under 6 months do not need to be grasped or restrained as firmly as toddlers or older children. At this age, excessive restraint increases their fear as well as muscle tautness. The recommended positioning for an infant is in a cuddle hold with parent/guardian, breastfeeding as appropriate. The cuddle position offers better psychological support and comfort for both the infant and the parent/guardian,[3] and the parent/guardian should be offered this position as a first choice (Figure 2.1).

If the parent/guardian is helping to hold the infant or child, ensure they understand what is expected of them and what will take place. Most vaccinators choose to quickly administer all the injections due and soothe the infant or child afterwards (see section 2.3.2 for soothing measures).

Figure 2.1: The cuddle position for infants

Vastus lateralis

To locate the injection site, undo the nappy, gently adduct the flexed knee and (see Figure 2.2):

- find the greater trochanter

- find the lateral femoral condyle

- section the thigh into thirds and run an imaginary line between the centres of the two markers (look for the dimple along the lower portion of the fascia lata).

The injection site is at the junction of the upper and middle thirds and slightly anterior to (above) the imaginary line, in the bulkiest part of the muscle.

Figure 2.2: The infant lateral thigh injection site

The needle should be directed at a 90-degree angle to the skin surface and inserted slightly anterior to (above) the junction of the upper and middle thirds. Inject the vaccine at a controlled rate. To avoid tracking, make sure all the vaccine has been injected before smoothly withdrawing the needle. Do not massage or rub the injection site afterwards. However, infants with a bleeding disorder may require firm pressure over the injection site without rubbing for at least 10 minutes.

Where three injections are required as at the 5-month immunisation event, two injections should be given into one vastus lateralis (DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib and PCV) separated by 2 cm, and the other injection (MenB) is given into the other vastus lateralis. See Figure 2.9.

BCG vaccine (administered by authorised vaccinators with BCG endorsement)

The reconstituted BCG vaccine is given by intradermal injection slightly above the insertion of the deltoid muscle on the lateral surface of the left arm. The infant’s arm should be gently but firmly supported (see Figure 2.3(a)). The syringe should be held with the needle bevel uppermost, parallel with the skin of the arm (see Figure 2.3(b)).

Figure 2.3: The infant BCG vaccination site, and how to support the infant’s arm and hold the syringe

Inject the vaccine slowly (see Figure 2.4(a)), then gradually withdraw the needle. The injection is given slowly to avoid leakage around the needle or vaccine being squirted. Safety glasses should be used to protect the eyes of those involved. If BCG vaccine is accidentally squirted into the eyes, wash them immediately with water. Following BCG vaccination a white weal should appear (see Figure 2.4(b)), which should subside in approximately 30 minutes. The vaccination site requires no swabbing or dressing.

Figure 2.4: The BCG vaccine being slowly injected, and a white weal appearing as the needle is gradually withdrawn

2.2.5. Young child vaccination (vastus lateralis or deltoid)

2.2.5. Young child vaccination (vastus lateralis or deltoid)

The choice between the two sites for IM injections from 12 months of age will be based on the vaccinator’s professional judgement, taking in account knowledge of the child and ease of restraint. Some vaccinators consider the vastus lateralis preferable for young children when the deltoid muscle bulk is small and because of the superficiality of the radial nerve. Discuss the options with the parent/guardian when making your decision. (See also ‘The 12- and 15-month immunisation events’ in section 2.2.7.)

The easiest and safest way to position and restrain a young child for a lateral thigh and/or deltoid injection is to sit the child sideways on their parent’s or guardian’s lap. The parent’s/guardian’s hand restrains the child’s outer arm and the child’s legs are either restrained between the parent’s/guardian’s legs or by placing a hand on the child’s outer knee or lower leg. Alternatively, the child may face their parent/guardian while straddling the parent’s/guardian’s legs (see Figure 2.5 and Figure 2.6). Keeping a firm hold will help to avoid needle scratches that can result if the child moves.

Figure 2.5: Cuddle positions for vastus lateralis or deltoid injections in children

Figure 2.6: The straddle position for vastus lateralis or deltoid injections in children

In the straddle position, both the deltoid and vastus lateralis muscle are likely to be more tense or taut, and the injection may therefore be more painful.

2.2.6. Older child, adolescent and adult vaccination (deltoid)

2.2.6. Older child, adolescent and adult vaccination (deltoid)

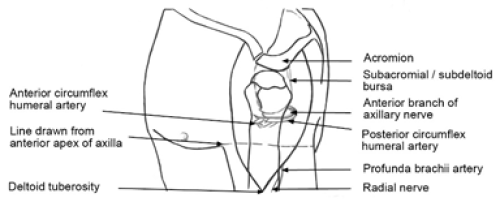

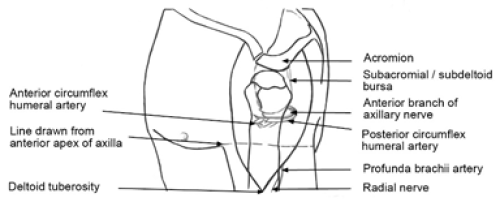

The deltoid muscle is located in the lateral aspect of the upper arm. The entire deltoid muscle must be exposed to avoid the risk of radial nerve injury (an injection at the junction of the middle and upper thirds of the lateral aspect of the upper arm may damage the nerve) (see Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7: Surface landmarks and structures potentially damaged by intramuscular injection in the upper limb

Reproduced with permission: Cook IF. 2011. An evidence-based protocol for the prevention of upper arm injury related to vaccine administration (UAIRVA). Human Vaccines 7(8): 845–8.

Reproduced with permission: Cook IF. 2011. An evidence-based protocol for the prevention of upper arm injury related to vaccine administration (UAIRVA). Human Vaccines 7(8): 845–8.

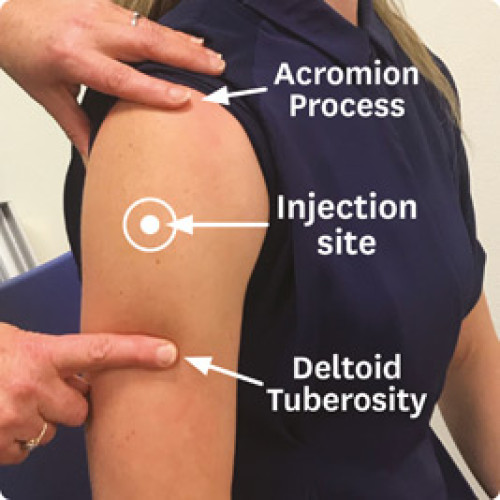

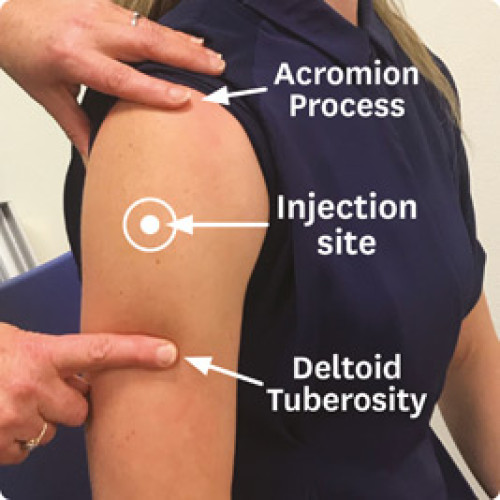

The volume injected into the deltoid should not exceed 0.5 mL in children and 1.0 mL in adults.

The vaccine recipient should be seated with their arm removed from the garment sleeve and hanging relaxed at their side. The vaccinator places their index finger on the vaccine recipient’s acromion process (the highest point on the shoulder) and their thumb on the vaccine recipient’s deltoid tuberosity (the lower deltoid attachment point).[7]

The injection site is midway between these anatomical landmarks. The vaccine should be deposited at the bulkiest part of the muscle, which usually in line with the axilla (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8: How to locate the deltoid site

2.2.7. Multiple injections at the same visit

2.2.7. Multiple injections at the same visit

A well-prepared and confident vaccinator will reassure the parent/guardian or whānau that giving concurrent vaccines is a safe and appropriate practice, avoiding multiple visits.

When more than one vaccine is scheduled at the same visit, it is recommended that vaccinators give all the scheduled vaccines at that visit. This particularly applies to the 12- and 15-month events (see below), when three vaccines are scheduled.

Multiple vaccines should not be mixed in a single syringe unless specifically licensed and labelled for administration in one syringe. A different needle and syringe should be used for each injection.

The 12-month and 15-month immunisation events

MMR1, PCV and MenB are the vaccines are scheduled at the 12-month immunisation event. It is preferable to give vaccines into separate sites. If the deltoid bulk is considered insufficient for IM injection, then two injections can be given into one vastus lateralis (MMR and PCV), and the MenB given into the other leg. Local tenderness is a potential reaction to MenB, such that, if given in the vastus lateralis may temporarily affect the infant’s mobility.

Suggested options for 12-months immunisation are given below.

|

Sufficient deltoid mass:

|

Insufficient deltoid mass:

|

To give two injections in the same limb, the vastus lateralis is preferred because of its greater muscle mass (see Figure 2.9). The injection sites should be on the long axis of the thigh and separated by at least 2 cm so that potential localised reactions will not overlap.

MMR2, varicella and Hib-PRP vaccines are scheduled at the 15-month event. When giving these vaccines, it is preferable to give one in each vastus lateralis and the third in the deltoid. When a fourth injection is required (eg, MenB catch-up), this should be given in the other deltoid.

The recommended vaccine administration sequence and location is:

- Hib-PRP: IM in left leg (vastus lateralis)

- Varicella: IM in left arm (deltoid)

- MMR: IM in right leg (vastus lateralis).

If parents/guardians request to split the vaccines given at the 15-month event, then providers are advised to give MMR and VV at the first visit, followed by Hib-PRP at the second visit.

Note: there is a risk that the patient may not return for the second visit when the 15‑month vaccines are split.

If MMR and VV are not given at the same visit (concurrently), then there should be an interval of at least four weeks between them. This interval is to avoid the response to the second vaccine being diminished due to interference from the response to the first vaccine (see section 2.1.5).

Multiple injections in the same muscle

When two injections are to be given in the same limb, the vastus lateralis is preferred because of its greater muscle mass (see Figure 2.9). The injection sites should be on the long axis of the thigh and separated by at least 2 cm so that localised reactions will not overlap.

If multiple injections in the deltoid are required, the sites should be separated by at least 2 cm.[8]

Figure 2.9: Suggested sites for multiple injections in the lateral thigh

2.3. Post-vaccination

2.3.1. Post-vaccination advice

2.3.1. Post-vaccination advice

Post-vaccination advice should be given both verbally and in writing. The advice should cover:

- which vaccines have been given and the injection sites, and whether the injections were IM or SC

- potential vaccine responses following immunisation (see Table 2.9) and what to do if these occur (eg, measures for relieving fever, when to seek medical advice)

- when the individual or parent/guardian should contact the vaccinator if they are worried or concerned

- contact phone numbers (including after-hours phone numbers).

Table 2.9: Potential vaccine responses

| Vaccine | Potential vaccine responses |

| DTaP- or Tdap-containing vaccine | Localised pain, redness and swelling at injection site Mild fever Being grizzly and unsettled Loss of appetite, vomiting, and/or diarrhoea Drowsiness Extensive limb swelling after multiple doses of a DTaP-containing vaccine |

| Hib-PRP | Localised pain, redness and swelling at the injection site Mild fever Being grizzly and unsettled |

| Hepatitis B | Very occasionally pain and redness at the injection site Nausea or diarrhoea |

| HPV | Fainting, especially in adolescents – this is an injection reaction, not a reaction to the vaccine Localised discomfort, pain, redness and swelling at the injection site Mild fever Headache |

| Influenza | Localised pain, redness and swelling at injection site Headache Fever |

| MenB | Localised pain, redness and tenderness at injection site Mild to moderate fever Irritability, sleep changes, loss of appetite in young children Headache, muscle aches and nausea in older children and adults |

| MMR | Measles component: Fever which lasts 1–2 days; rash (not infectious) 6–12 days after immunisation Mumps component: Parotid and/or submaxillary swelling 10–14 days after immunisation Rubella component: Mild rash, fever, lymphadenopathy, joint pain 1–3 weeks after immunisation |

| Pneumococcal | Localised pain, redness and swelling at injection site Mild fever Irritability, sleep changes Loss of appetite |

| Rotavirus | Diarrhoea and or vomiting may occur after the first dose Mild abdominal pain |

| Varicella | Localised pain, redness and swelling at injection site Mild fever Mild rash, possibly at the injection site (2–5 lesions, appearing 5–26 days after immunisation) |

2.3.2. Recommendations for fever and pain management

2.3.2. Recommendations for fever and pain management

The use of paracetamol (or ibuprofen) around the time of immunisation in anticipation of immunisation-related fever or localised pain occurring is only recommended routinely for infants and children aged under 2 years receiving MenB (Bexsero) vaccine. In this case, up to three doses of paracetamol (or ibuprofen) can be given prophylactically to reduce fever (see section 13.5.1). For immunisation events that do not include administration of MenB or for children over the age of two years receiving MenB, the use of paracetamol (or ibuprofen) around the time of immunisation in anticipation of immunisation-related fever or localised pain occurring is not generally recommended. However, use of these medicines is recommended if the child is distressed due to discomfort following immunisation.

Health care providers are encouraged to discuss with parents the possible immunisation responses and non-pharmaceutical management of fever or pain, as well as the role of medicines.

Fever

General fever-relieving measures include:

- giving extra fluids to drink (eg, more breastfeeds or water)

- reducing clothing if the baby is hot.

While a high fever alone does not need treatment, analgesics (paracetamol or ibuprofen) may be used for distress or pain in a febrile child.

Pain management and soothing measures

For breastfeeding infants, breastfeeding before, during and after the injection can provide comfort and pain relief.[3, 14]

Give the rotavirus vaccine 1–2 minutes before other immunisations; rotavirus vaccines contain sucrose that has been shown to reduce pain.[3, 14] The infant can then be breastfed (where possible) or held comfortably while the other immunisations are given.

For infants aged under 6 months, the 5 Ss (swaddling, side/stomach position, shushing, swinging and sucking) have been found to be effective for soothing and reducing pain after immunisations.[9]

Using age-appropriate distraction has been shown to reduce pain and distress.[3, 14] Examples include showing an interesting or musical toy to an infant, or encouraging an older child to blow using a windmill toy or bubbles. Electronic games/phone games can be useful for older children and teenagers. Do not rub the injection site after the injection, as it increases the risk of vaccine reactogenicity.

For infants and children, the use of a topical anaesthetic cream or patch has been found to be effective for immunisation pain management.[3, 14] Parents/guardians and those administering the vaccine should check the manufacturers’ recommendations before using topical anaesthetics. The correct dose for infants needs to be followed particularly carefully due to risk of methaemoglobinaemia. Topical anaesthetics may have a role in managing immunisation pain and anxiety, particularly for children who have had previous multiple medical interventions or needle phobias.

Following immunisation, if an infant or child is distressed by pain or swelling at the injection site, placing a cold, wet cloth on the area may help relieve the discomfort. Antipyretic analgesics (paracetamol or ibuprofen) may be used if the above measure does not relieve the child’s distress.

Table 2.10: Signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis

Table 2.10: Signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis

|

|

Signs and symptoms |

Severity |

|---|---|---|

|

Early warning signs (usually within a few minutes) |

Dizziness, perineal burning, warmth, pruritus, flushing, urticaria, nasal congestion, sneezing, lacrimation, angioedema |

Mild to moderate |

|

Angioedema, hoarseness (laryngeal oedema), dyspnoea, abdominal pain, vomiting, substernal pressure |

Moderate to severe |

|

|

Life-threatening symptoms (usually from soon after the injection to within 20 minutes after) |

Bronchospasm, stridor, collapse, hypotension, dysrhythmias |

Severe |

Table 2.11: Distinguishing anaphylaxis from a faint (vasovagal reaction)

Table 2.11: Distinguishing anaphylaxis from a faint (vasovagal reaction)

| Faint | Anaphylaxis | |

| Onset | Usually before, at the time, or soon after the injection | Soon after the injection, but there may be a delay of up to 30 minutes |

| System | ||

| Skin | Pale, sweaty, cold and clammy | Red, raised and itchy rash; swollen eyes and face; generalised rash |

| Respiratory | Normal to deep breaths | Noisy breathing due to airways obstruction (wheeze or stridor); respiratory arrest |

| Cardiovascular | Bradycardia; transient hypotension | Tachycardia; hypotension; dysrhythmias; circulatory arrest |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea/vomiting | Abdominal cramps |

| Neurological | Transient loss of consciousness; good response once supine/flat | Loss of consciousness; little response once supine/flat |

2.3.3. Anaphylaxis and emergency management

2.3.3. Anaphylaxis and emergency management

All vaccinators must be able to distinguish anaphylaxis from fainting, anxiety, immunisation stress-related responses (ISRR), breath-holding spells and seizures.

Anaphylaxis is a very rare,[10] unexpected and potentially fatal allergic reaction. It develops over several minutes and usually involves multiple body systems. Unconsciousness is rarely the sole manifestation and only occurs as a late event in severe cases. A strong central pulse (eg, carotid) is maintained during a faint (vasovagal syncope), but not in anaphylaxis.

In general, the more severe the reaction, the more rapid the onset. Most life-threatening adverse events begin within 10 minutes of vaccination. The intensity usually peaks at around one hour after onset. Symptoms limited to only one system can occur, leading to delay in diagnosis. Biphasic reactions, where symptoms recur 8 to 12 hours after onset of the original attack, and prolonged attacks lasting up to 48 hours have been described. All patients with anaphylaxis should be hospitalised.

Signs of anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is a severe adverse event of rapid onset, characterised by circulatory collapse. In its less severe (and more common) form, the early signs are generalised erythema and urticaria with upper and/or lower respiratory tract obstruction. In more severe cases, limpness, pallor, loss of consciousness and hypotension become evident, in addition to the early signs. Vaccinators should be able to recognise all the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis given in Table 2.10.

There is no place for conservative management of anaphylaxis. Early administration of adrenaline is essential (for more details, see Table 2.12).

Misdiagnosis of faints and other common causes of collapse as anaphylaxis may lead to inappropriate use of adrenaline. Misdiagnosis as a faint could also lead to a delay in the administration of adrenaline.

Vaccinators should therefore be able to distinguish anaphylaxis from fainting (vasovagal syncope), anxiety and breath-holding spells (see Table 2.11). Infants and babies rarely faint. Sudden loss of consciousness, limpness, pallor and vomiting (signs of severe anaphylaxis in children) should be presumed to be an anaphylactic reaction.

In adults and older children, the most common adverse event is a syncopal episode (fainting), either immediately or soon after vaccination. During fainting the individual suddenly becomes pale, loses consciousness and if sitting or standing will slump to the ground. Recovery of consciousness occurs within a minute or two. Fainting is sometimes accompanied by brief clonic seizure activity, but this generally requires no specific treatment or investigation if it is a single isolated event.

Immunisation stress-related response

Immunisation stress-related responses (ISRR) is a term used to cover a spectrum of responses to stress generated by immunisations.[11] These responses vary from fainting and hyperventilation through to dissociative neurological symptoms, which include non-epileptic seizures. They usually occur in individuals but have also been identified in clusters; this is often referred to as mass psychogenic illness. These stress responses are complex and involve both physiological and psychological factors. For more information see the WHO manual for health professionals.

Distinguishing a hypotonic-hyporesponsive episode from anaphylaxis

A hypotonic-hyporesponsive episode is a shock-like state defined by the sudden onset of limpness (muscle hypotonia) and decreased responsiveness, with pallor or cyanosis in infants and children aged under 2 years after immunisation.

A hypotonic-hyporesponsive episode can occur from 1 hour to 48 hours after immunisation, typically lasts less than 30 minutes, and resolves spontaneously.[12]

A hypotonic-hyporesponsive episode is a recognised serious reaction to immunisation and should be reported to CARM (see section 1.6.3).

Avoidance of anaphylaxis

Before immunisation:

- ensure there are no known contraindications to immunisation

- if in doubt about administering the vaccine, consult the individual’s GP or a paediatrician.

Individuals should remain under observation for 20 minutes following vaccination in case they experience an immediate adverse event requiring treatment. This observation period may vary for some vaccines and age groups.

Emergency equipment

Vaccinators, providers and quality managers are responsible for:

- ensuring emergency procedures are known by all staff

- practising emergency procedures regularly

- having an emergency kit (see Table 2.12) and adrenaline in every room where vaccinations/medications are given

- checking emergency kits regularly

- not giving vaccines when working alone.